Psychedelics: From Woodstock to Walgreens - Updated (2023)

"Psychedelic experience is only a glimpse of genuine mystical insight, but a glimpse which can be matured and deepened by the various ways of meditation in which drugs are no longer necessary or useful. If you get the message, hang up the phone. For psychedelic drugs are simply instruments, like microscopes, telescopes, and telephones. The biologist does not sit with eye permanently glued to the microscope, he goes away and works on what he has seen..."

– Alan Watts

Table of Contents

What Are Psychedelics?

The term “psychedelic” was first used by psychiatrist Humphry Osmond in 1956 during a discussion with Aldous Huxley, the famous author and pioneer of psychedelic consumption. The etymology of the word is derived from the Greek meaning “mind-manifesting”. A more robust definition of the word was developed by Grinspoon and Bakalar:

"a psychedelic drug is one which, without causing physical addiction, craving, major physiological disturbances, delirium, disorientation, or amnesia, more or less reliably produces thought, mood, and perceptual changes otherwise rarely experienced except in dreams, contemplative and religious exaltation, flashes of vivid involuntary memory and acute psychoses."

– Grinspoon and Bakalar (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies)

Notice that this definition excludes drugs like heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, and THC, all of which can produce psychedelic effects but are not their primary effect.

History of Psychedelic Use

Sacred ceremonies

Psychedelics have been regarded as sacred plants since the dawn of civilization, with the earliest known consumption of plants containing psychedelic agents occurring in 5000 BCE in Southeastern Algeria . The use of psychedelics to conjure religious experiences was universal amongst humans, as evidenced by depictions of sacred ceremonies centered on these mind-expanding substances found across the globe. The plants which contain these psychedelic agents include mushrooms, cacti, morning glory vines, and even some grasses. Psychedelic ceremonies have shaped many religions and are still used throughout the world.

Examples include:

- “Soma” found in Sanskrit texts of Hinduism, derived from the Amanita Muscaria mushroom (~1500 BCE)

- Ergot fungus used in the Eleusinian Mystery Rites of the Greeks, the active ingredient being similar to the synthetic LSD (“acid”) (~2000 BCE)

- Psylocibin mushrooms used in the town of Villar del Humo in Spain (earliest evidence of psychedelic mushrooms in Europe, ~4000 BCE)

- Peyote used by the Native Americans, found in the Shumla Caves (~3700 BCE)

- Modern day usage of psychedelics includes Ayahuasca in the Amazon (active ingredient is DMT), Peyote by the Native Americans in the Western USA, and the global use of Psilocybin.

Sacred ceremonies were (and are) typically led by a Shaman, a respected elder who plays the role of doctor, therapist, and priest. Along with administration of the psychedelic plants, the Shaman provides “non-drug” support to his “patient” to amplify and control the mind-enhancing effects of the compounds. The dreamlike states that the Shaman can invoke brings forth the shadows that lurk in the subconscious into the spotlight of the conscious mind. I have heard frequent users of psychedelics in religious contexts explain the experience as 10 years’ worth of therapy crammed into 4 hours… you are forced to confront your demons and reconcile your angst. These ceremonies are vital to preserving ancient cultures and should be respected as integral parts of religion Now that’s heavy stuff. Let’s move on to something a bit lighter…

The sacred shroom

Although Western medicine's first foray into psychedelics was focused on LSD, the use of natural psychedelic agents have been used to treat both mental and physical illnesses in ancient societies for thousands of years. Psychedelics have been regarded as sacred plants since the dawn of civilization, with the earliest known consumption of plants containing psychedelic agents occurring in 5000 BCE in Southeastern Algeria. The use of psychedelics to conjure religious experiences was universal amongst humans, as evidenced by depictions of sacred ceremonies centered on these mind-expanding substances found across the globe. The plants which contain these psychedelic agents include mushrooms, ayahuasca, cacti, morning glory vines, and even some grasses. Psychedelic ceremonies have shaped many religions and are still used throughout the world to invoke spiritual experiences (ayahuasca ceremonies are particularly en vogue these days, with Westerners flocking to the Amazon in Peru to receive the medicine under the direction of shamans... The authors of MedicalGold are also experienced users of psychedelics in therapeutic settings). Seven thousand years' of use is quite a testament to the power of plant-derived psychedelics.

None more so than the Psilocybe cubensis, the sacred shroom.

Psilocybe cubensis is a species mushroom containing the psychedelic compounds psilocybin and psilocin. Also known as "magic mushrooms" or "gold caps," psilocybe cubensis is the most well known psychedelic mushroom due to its ease of cultivation and ability to grow in many tropical geographies. Both psilocybin and psilocin are labeled as Schedule 1 drugs in the United States, but are legal in other countries (such as Brazil, Jamaica, and the Netherlands). The legal status of psilocybin-containing mushrooms is rapidly evolving, and the possession of magic mushrooms has been decriminalized in Santa Cruz and Oakland; Denver, CO; Somerville and Cambridge, Massachusetts; Washington D.C., and the entire state of Oregon). It should be noted that the cultivation, distribution, and sale of psychedelic mushrooms still remains illegal in most jurisdictions, with the exceptions of Oregon and California which legalized the use of mushrooms in clinical settings on February 1, 2021. Washington D.C. also legalized the cultivation and possession of "psychedelic and entheogenic fungi" on the same date The regulatory landscape is fragmented, confusing, and continuously evolving.

Learn more about what will propel this industry into main stream medical practice

Full legalization of psychedelics for recreational use in the United States will likely follow the same trajectory as cannabis, with more liberal jurisdictions paving the way. Unlike cannabis, the medical community is pouring a tremendous amount of resources into clinical trials for multiple neurological disorders, and even physiological diseases such as cancer and stroke.

Discovery of LSD

Psychedelic-based therapies are poised to completely shift the mental health treatment paradigm. Like the cannabis industry circa mid-2000s, the first movers who assume the risk of developing these Schedule 1 pharmaceuticals will be positioned to "mop up" a highly-fragmented sector once the market catches on and there is a rush to fund the most promising medical psychedelic companies. Even though medical psychedelics are considered a novel class of drug, plant-derived psychedelic substances (e.g., psilocybin derived from "magic mushrooms") have been used for thousands of years in ancient ceremonial settings to treat both physical and mental conditions. But it wasn't until the 1940's that psychedelic research started in the West. And it wasn't even on purpose.

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (“LSD”) is probably the most widely recognized psychedelic substance. Colloquially known as “acid”, LSD was first synthesized in 1938 at the Sandoz research labs in Basel, Switzerland, by Dr. Albert Hofmann. While conducting research into ergot, a fungus that grows on grains and was the cause of mass poisoning in the middle ages (“Saint Anthony’s fire”), Dr. Hofmann realized that the panic-inducing effects of ergot consumption could be attributed to specific alkaloids present in the plant. The basic group of the primary alkaloid (ergobasine) was discovered to be lysergic acid, and several modifications were made to produce LSD as it is known today (“LSD-25”, the 25th modification to the lysergic acid base). The first clinical applications of LSD-25 were tested on controlling blood flow loss in the uterus, but it was quickly determined that the synthetic LSD was not as effective as the naturally occurring substance in ergot. Dr. Hofmann abandoned his research until he accidentally ingested a microscopic amount of LSD via absorption through his skin. According to popular lore, Dr. Hofmann then took an interesting bike ride home during which he was not completely sure whether he was actually moving… upon examination by a medical doctor it was determined that Dr. Hofmann experiencing the full-blown effects of the first acid trip, characterized by pleasant visual distortions and intensely bright colors.

In a more formal laboratory setting, researchers at Sandoz Labs (Basel, Switzerland) discovered that LSD-25 induced a state of euphoria accompanied by visual distortions and enhanced sensory perception (1943). The exact mechanism of action was not fully understood until researchers discovered the role of serotonin in the brains of mammals ten years later (1953). LSD's chemical structure, along with the structures of many other tryptamine-based psychedelic molecules (we'll get to those in a minute), looks strikingly similar to serotonin's chemical structure. The following hypothesis was put forth: LSD's mechanism of action mimics that of serotonin by binding to the same receptors and eliciting a cascade of serotonergic neuronal signaling.

Government intervention

MK-Ultra

The LSD-25 compound was tested by other researchers at Sandoz for its potential medicinal benefits. Marketed under the name Delysid, Sandoz’s LSD-25 was approved for psychiatric use and disseminated to psychiatrists worldwide. Predicated on the large-scale manufacturing capabilities in the post-WWII 20th century, and the emerging field of psychiatric research and treatment, interest in LSD-25 skyrocketed and hit the public consciousnesses.

Much of the early research into using LSD-25 as a catalyst for inducing changes in brain states was conducted by the CIA in a project known as “MK-ULTRA”. The CIA speculated that LSD could be used as a “truth drug” to assist in interrogations, and in 1953 the agency was given formal approval to test a wide range of psychedelic substances as possible interrogation “enhancers” (LSD being the prime candidate). The MK-ULTRA story is fascinating, fraught with corruption and mysterious deaths, yet the conclusion of the program was uninspiring: LSD-25 is a very poor truth serum and the effects were largely unpredictable between recipients.

Meanwhile, psychiatrists were developing two new models of psychedelic-assisted therapy: psychedelic therapy and psycholytic therapy. Both paradigms involved the use of LSD in treatment, but psycholytic therapy was much a softer approach that involves substantially lesser amounts of LSD than psychedelic therapy, with the goal of bringing about gradual change in personality over the course of months. The underlying theory of psycholytic therapy was based upon Freudian psychoanalysis, with the idea that LSD served as a priming agent by inhibiting the portion of the brain responsible for the ego-identity. LSD was intended to break down the ego and render the patient in a naïve, infantile state of feeling, often associated with derealization and mystic experience. Contrastingly, psychedelic therapy was an attempt to wage total war on the brain using extremely high amounts of LSD dosed in a single session, with the goal of bringing about a symptomatic change in behavior (poorly defined). The original theory was that extremely high doses of LSD could shock alcoholic patients and scare them away from drinking permanently by giving them a horrific experience… but to the clinicians’ surprise the patients experienced very pleasant effects. Emphasis of psychedelic therapy switched from inducing a mystical type of experience to re-wiring the patient's brain at the direction of the therapist.

"Many people remember vaguely that LSD and other psychedelic drugs were once used experimentally in psychiatry, but few realize how much and how long they were used. This was nota quickly rejected and forgotten fad. Between 1950 and the mid-1960s there were more than a thousand clinical papers discussing 40,000 patients, several dozen books, and six international conferences on psychedelic drug therapy. It aroused the interest of many psychiatrists who were in no sense cultural rebels or especially radical in their attitudes."

– Grinspoon and Bakalar, 1979

"Turn on, Tune in, Drop out"

The popularization of LSD as a substrate for religious-like experiences in American culture was pioneered by the likes of Aldous Huxley, Gerald Heard, Timothy Leary, and Richard Alpert (later to be known as Ram Daas). Their collective work chronicled the psychonaut’s journey through time and space, blending Eastern philosophy with Western ideas. These writings were often written like a piece of “gonzo journalism”, the focus being on the author’s own lived experience. These first-person essays galvanized the public’s curiosity into using psychedelics to unlock latent mental bandwidth and enhance the sensory world.

"The really important facts were that spatial relationships had ceased to matter very much and that my mind was perceiving the world in terms of other than spatial categories. At ordinary times the eye concerns itself with such problems as where? — how far? — how situated in relation to what? In the mescaline experience the implied questions to which the eye responds are of another order. Place and distance cease to be of much interest. The mind does its perceiving in terms of intensity of existence, profundity of significance, relationships within a pattern."

- Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception

Back in the day, loose regulations around controlled substances allowed psychiatrists to give people LSD with little oversight in questionable environments, leading to a surge in recreational use beginning the early 1960s. FDA regulations began to tighten around the same time, and the introduction of the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendment (1962) forced Sandoz to limit the supply of LSD to physicians at the National Institute of Mental Health. Not long after, the 1965 Drug Control Amendment forced Sandoz to stop supplying LSD entirely (it was later deemed a Schedule 1 substance by the FDA, 1970). Combined with the loss of patent protection for Delysid, the financial incentive for Sandoz labs to continue manufacturing their proprietary LSD-25 was completely destroyed. As the counter-culture movement of the ‘60s took off, illegal manufacturing and distribution of LSD kept the hippy generation satisfied.

State-of-the-Science

Mechanism of action

The discovery of the psychedelic effects of LSD in 1943 was followed by the detection of serotonin in the brains of mammals (1953). Comparison of the serotonin structure with that of LSD revealed a striking similarity in the scaffold of the molecules. Could LSD’s mechanism of action in the brain rely on the same neuronal pathways that serotonin signals through? It was quickly discovered that the mind-altering effects of LSD were attributed to an interference in serotonin signaling in the brain (via competition for the 5-HT2 serotonin receptors). This discovery catapulted research into the role of serotonin in neuroscience.

Medical psychedelics can largely be classified into 2 groups: indolealkylamines (psilocybin, LSD, and DMT) and phenylalkylamines (MDMA, mescaline, and amphetamine analogs) [13].

Indolealkylamines are based on the core serotonin structure and bind to the serotonin receptors in the brain. Notice how similar psilocybin and DMT are to the core serotonin structure. These two compounds are grouped together and known as tryptamines.

Phenylalkylamines are based on the dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine chemical structures, and induce psychedelic effects through those neuronal pathways.

Clinical research

The clinical research on psychedelics of the 20th century ended with the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Fortunately, the recent resurgence in interest into the medical benefits of psychedelics has led to the renewal of experimentation in humans. On March 5, 2019, esketamine (Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a J&J company) became the first approved psychedelic drug by the FDA for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Delivered as a nasal spray, esketamine is a pure ketamine substance that has been indicated for major depressive disorder (MDD). Some patients report immediate relief from suicidal ideations, although the greater scientific community is not completely convinced due to the small effect size.

Clinicians are also promoting the use of psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms) as a means to increase the patient’s receptivity to talk therapy. A quick search of the ClinicalTrials.gov site reveals that there are 53 ongoing human clinical studies on the therapeutic effects of psilocybin for a wide range of diseases, from anorexia to cancer. Leading the way, a Phase 2 study (N=80; NCT03866174) investigating the antidepressive effects of a single-dose psilocybin administration is currently being conducted by the Usona Institute and was recently granted “Breakthrough Designation”. Compass Pathways is also currently conducting a Phase 2b study (N=216, NCT03775200) for the use of psilocybin in treating treatment resistant depression.

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelics Studies (MAPS) recently raised $30M for its MDMA study in the treatment of PTSD . Granted the “Breakthrough Therapy” designation by the FDA. MAPS’ Phase 3 clinical trials are ongoing with expected approval as early as 2022 . There are 90 other trials currently being conducted on MDMA.

Clinical research has reached a critical mass in early 2023, with multiple companies advancing LSD, MDMA, DMT, and psilocybin drug assets into late-stage trials. We can expect approval of the first MDMA pharmaceutical later this year and the release of plenty of clinical trial data throughout the year. Click on the link below to learn more about these late-stage trials.

Top 5 Psychedelic Late-Stage Clinical Trials To Keep An Eye On in 2023

Data does not lie

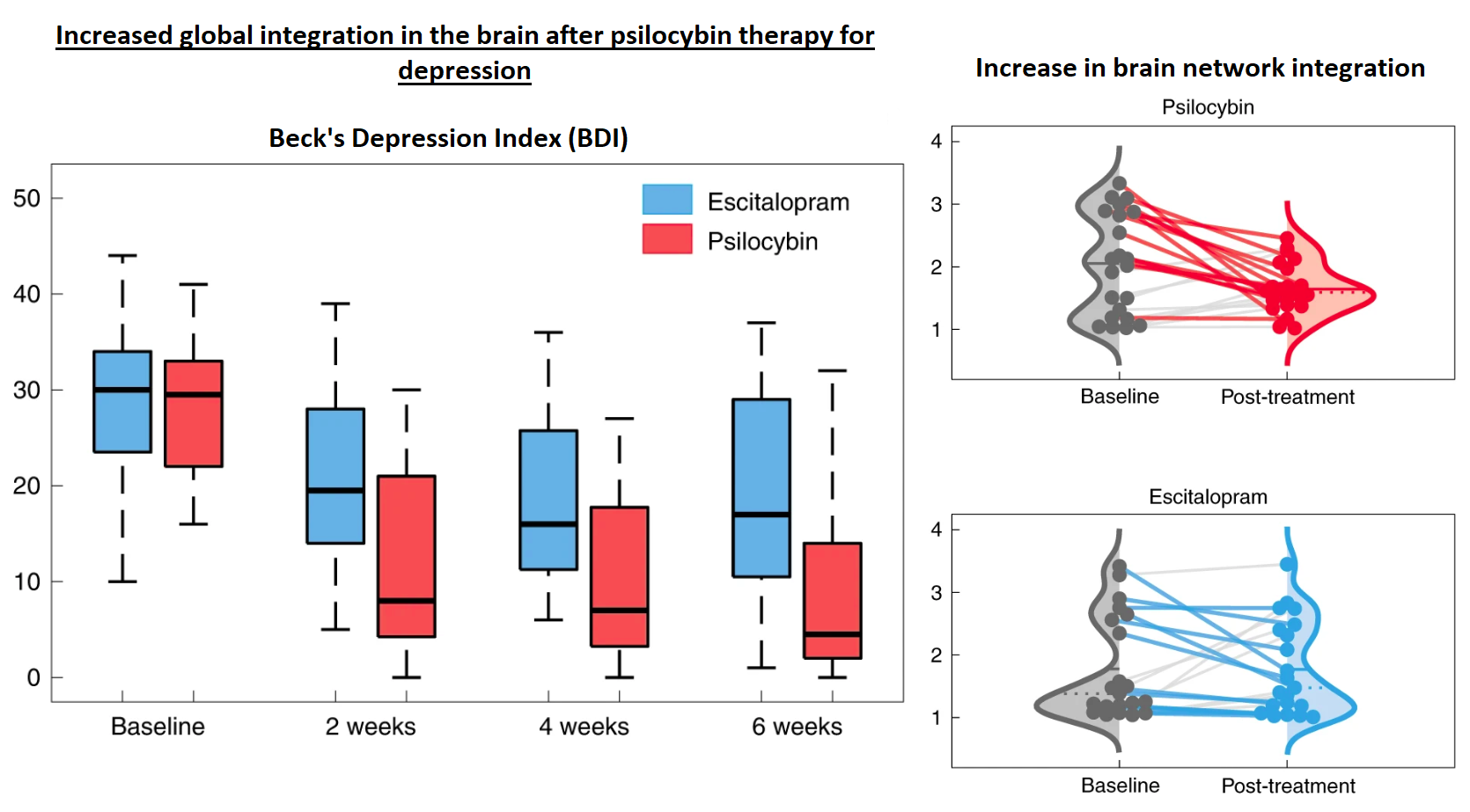

One prevailing hypothesis is that depression is caused by "disintegration of functional neural networks," meaning regions of the brain that are supposed to activate together no longer do so. Perhaps the solution is to "jump start" the brain to reform these neural pathways?

In a recent study led by Richard Daws and Christopher Timmermann, researchers at Imperial College and Kings College (London, UK) examined the impact of orally administered psilocybin (10 and 25mg doses) on brain network organization using functional MRI (fMRI) to quantify neuronal signaling. The fMRI signals were correlated with antidepressant effects on patients as measured by Beck's depression inventory in a Phase 2 study. They discovered that the serotonin receptor 5-HT2A mediated neuronal networks became more interconnected after psilocybin dosing, indicating that psilocybin has an impact on new neural pathway formation (i.e., neuroplasticity). Importantly, they did not see these same changes in patients dosed with escitalopram, a commonly prescribed selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) for depression [Link].

Figure 1: Beck's depression inventory (BDI) score and changes in brain network connectivity. The results show a substantial decrease in depression (as measured by a decrease in BDI score) associated with psilocybin treatment compared to escitalopram. This clinically meaningful outcome is associated with an increase in brain network integration (i.e., less "modularity," more connectivity), as measured by real-time fMRI signal [Link].

Another clinical study on psilocybin conducted by Dr. Alan Davis at the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) also found a meaningful decrease in depressive symptoms (this time measured with a different depression scoring system, the GRID-HAMD scale) over a similar time-course (within four weeks). Importantly, psilocybin treatment also demonstrated a long lasting antidepressant effect induced by psilocybin-assisted therapy at a 12 month follow-up [Link].

Figure 2: Decrease in GRID Hamilton depression rating scale scores within four weeks post-treatment. Patients were divided into two cohorts. The first group received two doses of orally administered psilocybin (20mg/70kg body weight), one week apart, immediately upon the study start ("Immediate Treatment"). To serve as a control, the second group of patients received the same doses seven weeks after the first group ("Delayed Treatment"). Both groups of patients were scored using the GRID Hamilton Scale at weeks 5 and 8, and the results showed that the patients that had received their doses at the beginning of the study (Immediate Treatment) had a statistically significant reduction in GRID-HAMD score that was ~2.5x greater than the patients who had not received their treatment yet (Delayed Treatment). Additionally, the authors reported only mild-to-moderate side effects, such as headache and having to deal with challenging emotions... a far cry from the suicidal ideation, impotence, and anhedonia that many antidepressants cause [Link].

Simply put, psilocybin is capable of rewiring your brain, and traditional antidepressants are not. This is what researchers have suspected for years; psychedelics are a "jump start" for the brain. Turns out they were right.

Clinicians are also promoting the use of psilocybin as a means to increase the patient’s receptivity to talk therapy. A quick search of the ClinicalTrials.gov site reveals that there are 53 ongoing human clinical studies on the therapeutic effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy for a wide range of diseases, from anorexia to cancer. A Google Scholar returns over 5,000 published papers on the topic since 2018.

Here are the facts: the science is sound, the market is enormous, and the first psilocybin therapy to gain approval will be a multi-billion dollar drug.

OUR PICKS IN THE MEDICAL PSYCHEDELIC SECTOR

- PharmAla Biotech: Bringing MDMA To A Clinic Near You

- Numinus Wellness: Integrating The Medical Psychedelic Industry

- MindMed: Developing a holistic approach to treating mental illness with psychedelic compounds

- Cybin Inc: Transforming "Psychedelics to Therapeutics™" With Psilocybin and DMT

- TRYP Therapeutics: The Next Wave of Psychedelic Drug Development Beyond Mental Health

DISCLAIMER:

The work included in this article is based on current events, technical charts, company news releases, and the author’s opinions. It may contain errors, and you shouldn’t make any investment decision based solely on what you read here. This publication contains forward-looking statements, including but not limited to comments regarding predictions and projections. Forward-looking statements address future events and conditions and therefore involve inherent risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from those currently anticipated in such statements. This publication is provided for informational and entertainment purposes only and is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Always thoroughly do your own due diligence and talk to a licensed investment adviser prior to making any investment decisions. Junior resource and biotechnology companies can easily lose 100% of their value so read company profiles on www.SEDARplus.ca for important risk disclosures. It’s your money and your responsibility.